ABSTRACT

- Hypertension is a common condition among older adults, and blood pressure (BP) control is effective for preventing cardiovascular morbidity and mortality even among the oldest-old adults. However, the optimal target BP for older patients with hypertension has been a subject of debate, with previous clinical trials providing conflicting evidence. Determining the optimal target BP for older adults is a complex issue that requires considering comorbidities, frailty, quality of life, and goals of care. As such, BP targets should be individualized based on each patient's unique health status and risk factors, and treatment should be closely monitored to ensure that it is effective and well-tolerated. The benefits and risks of intensive BP control should be carefully weighed in the context of the patient's overall health status and treatment goals. Ultimately, the decision to pursue intensive BP control should be made through shared decision-making between patients and their healthcare providers.

-

Keywords: Aged; Blood pressure; Cardiovascular diseases; Hypertension

INTRODUCTION

- Hypertension is a common condition among older individuals, and it increases the risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. As the elderly population grows, it becomes increasingly critical to effectively manage elevated blood pressure (BP). However, determining the optimal BP target for older adults remains a topic of debate due to conflicting evidence from previous clinical trials. Recent trends suggest a move towards more aggressive BP control with lower BP targets for older adults, but concerns remain about the potential risks associated with intensive BP reduction, especially among frail older adults [1,2]. As a result, determining the optimal target BP for older adults is still uncertain, and treatment must be individualized based on patient-specific characteristics.

- This review aims to provide an objective overview of the current evidence and unresolved issues regarding target BP in older adults, including the benefits and risks associated with different targets. Additionally, I will discuss the challenges and considerations involved in personalizing hypertension treatment for older adults to enhance clinical decision-making and improve patient outcomes.

THE CURRENT STATUS AND IMPORTANCE OF HYPERTENSION AMONG OLDER ADULTS

- The prevalence of hypertension among older adults varies among countries, but it generally increases with age [3,4]. Hypertension is a highly prevalent chronic condition among older adults, and it affects a significant proportion of the adult population aged 65 years or older. For example, in the United States, the prevalence of hypertension is around 77% among adults aged 65 years and older, according to data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2015–2018 [3]. In Korea, the prevalence of hypertension among adults aged 65 years and older was reported to be ≥60% in men and ≥70% in women [5].

- According to the Korea Hypertension Fact Sheet 2022, the percentage of older patients with hypertension has increased steadily over time [6]. The proportion of the elderly population with hypertension was 22.5% in 1998, but it reached 39.6% in 2020. However, the proportion of treated and controlled hypertension among older adults has also increased significantly. In 1998, only 6.6% of older adults with hypertension were effectively managed, but this figure has increased to almost 60%. The awareness, treatment, and treatment adherence rates have also improved more rapidly among older adults with hypertension than among their younger counterparts. Nonetheless, it is worth noting that there has been a recent decline in awareness, treatment, and control rates among male hypertension patients aged 80 years or older.

- Hypertension has serious effects on older adults, including an increased risk of heart failure, atrial fibrillation, chronic kidney disease, coronary heart disease, and stroke. Older adults with hypertension are also at higher risk of developing cognitive decline and dementia [7,8]. Hypertension also exacerbates other age-related health conditions, such as vision loss, and can negatively impact overall quality of life.

- Additionally, older adults may have an increased risk of adverse drug events; thus, more careful management is required to avoid adverse effects such as falls, acute kidney injury, and cognitive impairment. Furthermore, hypertension is often asymptomatic, meaning that it can go unnoticed and untreated for years, leading to serious health consequences. However, effective BP control can help reduce the risk of serious health problems such as heart disease, stroke, kidney disease, and dementia. Additionally, BP control may help prevent or delay the onset of these conditions, thereby improving overall health outcomes in older adults. However, determining the optimal target BP for older adults is a complex issue that requires considering the individual patient's health status and goals of care.

THE BENEFITS AND RISKS OF INTENSIVE BP REDUCTION AMONG OLDER HYPERTENSIVE PATIENTS

- BP control must be carefully managed in older adults, as they may be more vulnerable to the adverse effects of both high and low BP. This includes an increased risk of falls, cognitive impairment, and other health problems [9].

- The optimal BP target has been a subject of extensive debate among older patients with hypertension. It is important to establish the target BP in older adults because they are a unique population with specific physiological changes that can impact their BP regulation. In addition, frail older adults’ increased vulnerability should be considered during treatment [10].

- Determining the appropriate BP target is critical because hypertension can have significant negative health consequences for older adults, including an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, stroke, and kidney damage. However, there are also potential risks associated with intensive BP control, particularly in older adults, who may be more vulnerable to adverse events associated with intensive BP reduction. Therefore, understanding the risks and benefits of different BP targets and individualizing treatment based on patient characteristics is necessary to ensure that older adults with hypertension receive appropriate and effective care to reduce the risk of complications and improve their quality of life.

- In addition, a cost-effectiveness analysis should be performed related to intensive BP reduction, because hypertension in older adults is a very prevalent condition, and the risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes or treatment-related events is substantial [11].

EVIDENCE FOR THE OPTIMAL BP TARGET FROM RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIALS

- Several randomized controlled trials have been conducted to investigate the optimal BP targets for older adults (Table 1) [12-14]. The optimal target BP for older adults may depend on various factors such as age, overall health status, and the presence of other medical conditions. However, several clinical trials have investigated BP targets for older adults, and the general consensus is that blood pressure should be controlled to a level that is appropriate for each individual based on their overall health status and risk factors.

- JATOS

- Japanese Trial to Assess Optimal Systolic Blood Pressure in Elderly Hypertensive Patients (JATOS) was a clinical trial conducted in Japan that aimed to determine the optimal target systolic BP (SBP) for elderly patients with hypertension [12]. The study enrolled a total of 4,508 patients with hypertension aged 65 to 85 years, with an SBP of 160 to 199 mmHg. The participants were randomly assigned to a mild treatment group with a target SBP of 140 to 160 mmHg or a strict treatment group with a target SBP of less than 140 mmHg. The risk of the primary outcome, a composite of the incidence of cerebrovascular disease, cardiovascular disease, and renal failure, was similar in both groups. There was no significant difference in drug-related safety events. However, there was a significant interaction between age and treatment for the primary endpoint. The incidence of the primary endpoint tended to be lower in the strict treatment group than in the mild treatment group in the younger patients, whereas the opposite trend was observed in the older patients. Based on these findings, the study concluded that strict BP control failed to show clinical benefits among older patients, but different effects associated with age should be considered.

- SPRINT

- Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) investigated the effects of intensive BP control with a target SBP of less than 120 mmHg compared to standard BP control with a target SBP of less than 140 mmHg in adults aged 50 years and older with hypertension [15]. The trial found that the intensive BP control group had a lower risk of cardiovascular events and mortality compared to the standard BP control group. However, intensive BP control may also increase the risk of adverse events such as hypotension, electrolyte abnormalities, and acute kidney injury, particularly in older adults. Among elderly patients aged over 75 years, the benefit of intensive BP control was significant, and intensive BP reduction decreased the incidence of mortality and cardiovascular outcomes [13]. Interestingly, the benefits were also observed in physically frail patients. In addition, intensive BP reduction therapy significantly decreased the risk of probable dementia [16]. In the final report of the study, the researchers stated that adverse events such as hypotension and syncope were more common among participants with chronic kidney disease, frailty, or older age; however, there was no age-by-treatment interaction for these events [17].

- STEP

- Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial in Elderly Patients (STEP) was a randomized controlled trial conducted in China to investigate the effect of intensive BP control on cardiovascular events among older adults with hypertension [14]. The trial included over 9,000 participants aged 60 to 80 years with hypertension who were at high risk of cardiovascular events. The participants were randomly assigned to receive either standard BP control with a target SBP of 130 to 150 mmHg or intensive BP control with a target SBP of 110 to 130 mmHg. The trial found that the intensive BP control group had a lower incidence of a composite of stroke, acute coronary syndrome, acute decompensated heart failure, coronary revascularization, atrial fibrillation, and cardiovascular death than the standard BP control group. The results for safety and renal outcomes did not differ significantly between the two groups, except for the incidence of hypotension, which was higher in the intensive treatment group.

META-ANALYSES OF PREVIOUS STUDIES

- Several meta-analyses have examined the optimal target BP for older adults. Xie et al. [18] published an up-to-date systematic review and meta-analysis regarding the effects of intensive BP reduction on cardiovascular and renal outcomes. They analyzed data from 19 randomized controlled trials involving over 44,000 participants and found that intensive BP reduction (mean BP of 133/76 mmHg) decreased the risk of major cardiovascular events and mortality compared to standard BP reduction (mean BP of 140/81 mmHg). The absolute benefits were greatest among patients with high cardiovascular risk, including those with vascular disease, renal disease, or diabetes. Serious adverse events associated with BP reduction were only reported in six trials, with an event rate of 1.2% per year in participants who received intensive BP reduction, compared with 0.9% in those who received standard treatment [18].

- Systematic reviews and meta-analyses including only older patients with hypertension have been published as well. Bavishi et al. [2] reviewed the outcomes of intensive BP reduction in older patients with hypertension and reported that intensive BP control (SBP<140 mmHg) decreased major adverse cardiovascular events (29% reduction), including cardiovascular mortality (33% reduction) and heart failure (37% reduction).

- Weiss et al. [19] also conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of the benefits and harms of intensive BP treatment in adults aged 60 years or older. They analyzed 21 randomized controlled trials comparing BP targets or treatment intensity, and three observational studies that assessed harms. They concluded that six trials yielded low- to moderate-strength evidence that lower targets (≤140/85 mmHg) were associated with marginally significant decreases in cardiac events (18% reduction) and stroke (21% reduction) and nonsignificant reductions in mortality. Interestingly, lower BP targets did not increase falls or cognitive decline but were associated with hypotension, syncope, and a greater medication burden.

- Another meta-analysis by Takami et al. [20] concluded that intensive antihypertensive regimens targeting SBP <140 mmHg did not significantly reduce the risk of a composite of cardiovascular diseases compared to less intensive treatments but did reduce the risk of death without increasing adverse events in patients aged 70 years or older. These findings support the benefit of intensive treatment targeting SBP to ≤140 mmHg in the elderly.

- A meta-analysis regarding the effect of intensive versus standard BP reduction therapy on cognitive decline and dementia has been published [21]. The results showed that there was no significant association between BP reduction and a lower risk of cognitive decline, dementia, or mild cognitive impairment. However, the certainty of this evidence was rated low because of the limited sample size, the risk of bias of the included trials, and the observed statistical heterogeneity. Finally, a systematic review and individual participant-based meta-analysis was performed regarding the effect of intensive BP reduction on orthostatic hypotension [22]. In contrast to current beliefs, intensive blood pressure-lowering treatment decreased the risk for orthostatic hypotension. Accordingly, the researchers suggested that orthostatic hypotension, before or in the setting of more intensive BP treatment, should not be viewed as a reason to avoid or de-escalate treatment for hypertension.

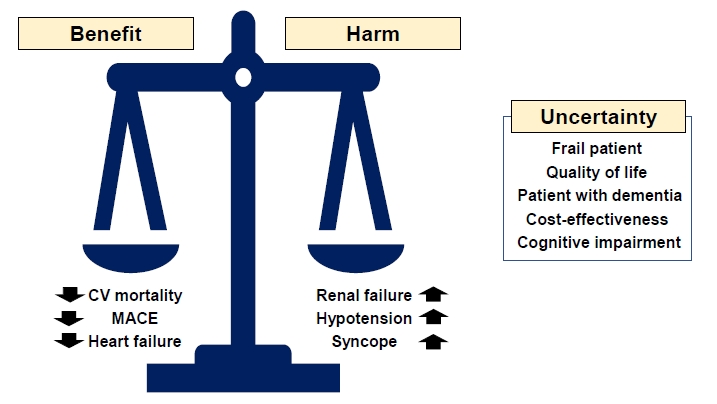

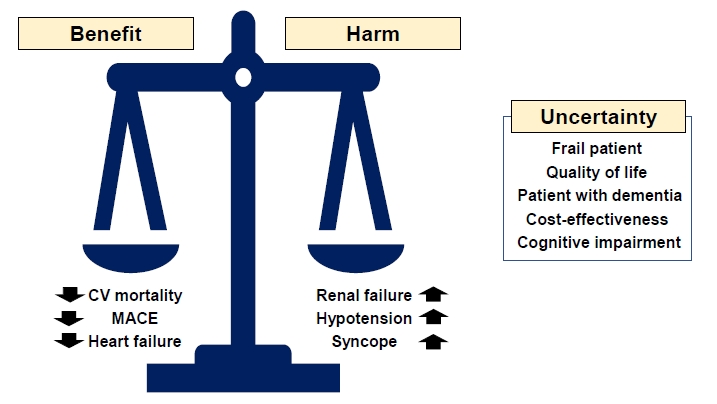

- While these meta-analyses provide important insights into the optimal target BP for older adults, there is still ongoing debate and uncertainty (Fig. 1). Of particular note, older patients with frailty, disability, or multimorbidity and institutionalized patients were excluded from randomized controlled trials; thus, the individualized treatment based on patient characteristics is necessary.

CURRENT GUIDELINES REGARDING THE TARGET BP FOR OLDER ADULTS

- The current guidelines regarding target BP in older patients vary among countries. However, in general, the recommendation for older patients with hypertension is to aim for a target SBP of less than 140 mmHg (Table 2) [23-26].

- The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines from 2017 recommended a BP target of less than 130/80 mmHg for adults aged 65 years or older [23]. Meanwhile, the European Society of Cardiology/European Society of Hypertension (ESC/ESH) guidelines from 2018 recommended a target BP of 130–139/70–79 mmHg for older adults, although a more conservative target may be appropriate for older adults who are frail or have multiple comorbidities [24].

- In Korea, the 2018 Korean Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension recommended a target BP of less than 140/90 mmHg for older adults aged 65 years or older with hypertension [26,27]. However, for older adults with comorbidities such as diabetes or chronic kidney disease, a lower target of less than 130/80 mmHg may be appropriate. The 2019 Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension recommended a target BP of less than 130/80 mmHg for patients with hypertension aged younger than 75 years and less than 140/90 mmHg for patients aged 75 and over [25].

- It is important to note that the specific target BP may vary depending on an individual's overall health status, medical history, and other individual factors. It is recommended to individualize and adjust BP targets over time as needed based on an individual's response to treatment and overall health status.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS: FRAILTY AND BP VARIABILITY

- Frail older adults are a unique population with specific healthcare needs, including the management of hypertension. The effect of BP control in this population has been a matter of debate, with conflicting evidence and concerns about the potential risks of treatment [28].

- Studies have shown that effective BP control in frail older adults may reduce the risk of cardiovascular events and improve outcomes. For example, SPRINT found that intensive BP control reduced the risk of cardiovascular events and mortality, including in subgroups of older adults with frailty.

- In general, a BP target of less than 150/90 mmHg is recommended for most older adults, including frail individuals. However, there are concerns about the potential risks of BP control in frail older adults. Intensive BP control may increase the risk of adverse events such as hypotension, falls, and acute kidney injury, particularly in this population. Frail older adults may also have multiple comorbidities and complex medication regimens, which may increase the risk of drug-drug interactions and adverse events [29]. Accordingly, close monitoring of BP and medication adjustments may also be necessary to achieve optimal BP control in these patients without causing harm. It is important for healthcare providers to consider the potential benefits and risks of BP control in frail older adults and to involve patients and their families in the decision-making process.

- BP variability refers to the natural fluctuations in BP levels over time. In older adults, BP variability may become more pronounced due to age-related changes in the cardiovascular system, as well as the presence of other health conditions such as frailty, diabetes, autonomic dysfunction, and neurodegenerative disease [30].

- Studies have shown that high BP variability in older adults may be associated with an increased risk of adverse health outcomes, such as stroke, cognitive decline, and mortality [31]. In addition, BP variability may have an impact on the effectiveness of BP management strategies, including the use of medications and lifestyle modifications.

- Given the potential health implications of BP variability in older adults, it is important for healthcare professionals to monitor BP levels and fluctuations over time. This may involve regular BP measurements, as well as the use of additional tools such as ambulatory BP monitoring and home BP monitoring to track changes in BP throughout the day.

CONCLUSIONS

- BP control is important for older adults with hypertension, but the optimal target BP for this population remains a subject of ongoing research and debate. Healthcare providers should work to individualize treatment and closely monitor patients to ensure that treatment is effective and well-tolerated, while minimizing the risks of adverse events.

ARTICLE INFORMATION

-

Ethics statements

Not applicable.

-

Conflicts of interest

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

-

Funding

This study was supported by a research grant from the Korea National Institute of Health (No. 2021-ER0901, 2021–2023).

Fig. 1.Benefits, harms, and uncertainties associated with intensive blood pressure reduction. CV, cardiovascular; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events.

Table 1.Randomized controlled trials targeting different BP targets in older patients with hypertension

|

Trial |

Target population |

Follow-up (yr) |

Target SBP goal (mmHg) |

Achieved BP (mmHg) |

Primary outcome |

Secondary outcome |

BP difference (mmHg) |

Main result |

|

Intervention |

Control |

Intervention |

Control |

|

JATOS [12] |

Adults aged 65–85 yr with hypertension |

2 |

<140 |

<140–160 |

135.9/74.8 |

145.6/78.1 |

Composite of cerebrovascular, CV disease, and renal failure |

All-cause mortality and safety problems |

9.7/3.3 |

No difference in the primary outcome, but a significant interaction between age and treatment was observed. |

|

SPRINT [13]a)

|

Adults aged ≥75 yr with hypertension |

3.14b)

|

<120 |

<140 |

123.4 |

134.8 |

Composite of CV events |

All-cause mortality and the composite of all-cause mortality and the primary outcome |

11.4/5.2 |

Intensive BP control reduced CV events by 34% and all-cause mortality by 33%. |

|

STEP [14] |

Adults aged 60–80 yr with hypertension |

3.34b)

|

<110–130 |

<130–150 |

126.7/76.4 |

135.9/79.2 |

Composite of stroke, acute coronary syndrome, acute decompensated heart failure, coronary revascularization, atrial fibrillation, CV death |

Components of the primary outcome, all-cause mortality, and renal outcomes |

9.2 |

Intensive BP control reduced the primary outcome by 26%. |

Table 2.Recommended target BP in patients with diabetes according to current guidelines

|

Characteristic |

2017 ACC/AHA [23] |

2018 ESC/ESH [24] |

2019 JSH [25] |

2022 KSH [26] |

|

Definition of older patients |

≥65 yr |

Elderly, 65–79 yr |

≥75 yr |

≥65 yr |

|

|

Very old, ≥80 yr |

|

|

|

BP threshold for drug treatment |

≥130/80 mmHg |

Elderly, ≥140/90 mmHg |

≥140/90 mmHg |

SBP, ≥140 mmHg (≥160 mmHg for ≥80 yr or frail older patients) |

|

|

Very old, ≥160/90 mmHg |

|

|

|

BP target |

<130/80 mmHg |

SBP, 130–139 mmHg |

<130/80 mmHg (65–74 yr) |

SBP, <140 mmHg |

|

|

DBP, 70–79 mmHg |

<140/90 mmHg (≥75 yr) |

|

REFERENCES

- 1. Benetos A, Petrovic M, Strandberg T. Hypertension management in older and frail older patients. Circ Res 2019;124:1045–60.ArticlePubMed

- 2. Bavishi C, Bangalore S, Messerli FH. Outcomes of intensive blood pressure lowering in older hypertensive patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:486–93.ArticlePubMed

- 3. Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, Alonso A, Beaton AZ, Bittencourt MS, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics: 2022 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022;145:e153–639.ArticlePubMed

- 4. NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in hypertension prevalence and progress in treatment and control from 1990 to 2019: a pooled analysis of 1201 population-representative studies with 104 million participants. Lancet 2021;398:957–80.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 5. Lee JH, Kim KI, Cho MC. Current status and therapeutic considerations of hypertension in the elderly. Korean J Intern Med 2019;34:687–95.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 6. Korean Society of Hypertension (KSH); Hypertension Epidemiology Research Working Group. Korea hypertension fact sheet 2022. KSH; 2022

- 7. Ungvari Z, Toth P, Tarantini S, Prodan CI, Sorond F, Merkely B, et al. Hypertension-induced cognitive impairment: from pathophysiology to public health. Nat Rev Nephrol 2021;17:639–54.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 8. Hajjar I, Quach L, Yang F, Chaves PH, Newman AB, Mukamal K, et al. Hypertension, white matter hyperintensities, and concurrent impairments in mobility, cognition, and mood: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Circulation 2011;123:858–65.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 9. Benetos A, Bulpitt CJ, Petrovic M, Ungar A, Agabiti Rosei E, Cherubini A, et al. An expert opinion from the European Society of Hypertension-European Union Geriatric Medicine Society Working Group on the management of hypertension in very old, frail subjects. Hypertension 2016;67:820–5.ArticlePubMed

- 10. Rivasi G, Tortu V, D’Andria MF, Turrin G, Ceolin L, Rafanelli M, et al. Hypertension management in frail older adults: a gap in evidence. J Hypertens 2021;39:400–7.ArticlePubMed

- 11. Liao CT, Toh HS, Sun L, Yang CT, Hu A, Wei D, et al. Cost-effectiveness of intensive vs standard blood pressure control among older patients with hypertension. JAMA Netw Open 2023;6:e230708.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 12. JATOS Study Group. Principal results of the Japanese trial to assess optimal systolic blood pressure in elderly hypertensive patients (JATOS). Hypertens Res 2008;31:2115–27.ArticlePubMed

- 13. Williamson JD, Supiano MA, Applegate WB, Berlowitz DR, Campbell RC, Chertow GM, et al. Intensive vs standard blood pressure control and cardiovascular disease outcomes in adults aged ≥75 years: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016;315:2673–82.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 14. Zhang W, Zhang S, Deng Y, Wu S, Ren J, Sun G, et al. Trial of intensive blood-pressure control in older patients with hypertension. N Engl J Med 2021;385:1268–79.ArticlePubMed

- 15. SPRINT Research Group, Wright JT Jr, Williamson JD, Whelton PK, Snyder JK, Sink KM, et al. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2103–16.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 16. SPRINT MIND Investigators for the SPRINT Research Group, Williamson JD, Pajewski NM, Auchus AP, Bryan RN, Chelune G, et al. Effect of intensive vs standard blood pressure control on probable dementia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2019;321:553–61.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 17. SPRINT Research Group, Lewis CE, Fine LJ, Beddhu S, Cheung AK, Cushman WC, et al. Final report of a trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med 2021;384:1921–30.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 18. Xie X, Atkins E, Lv J, Bennett A, Neal B, Ninomiya T, et al. Effects of intensive blood pressure lowering on cardiovascular and renal outcomes: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2016;387:435–43.ArticlePubMed

- 19. Weiss J, Freeman M, Low A, Fu R, Kerfoot A, Paynter R, et al. Benefits and harms of intensive blood pressure treatment in adults aged 60 years or older: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2017;166:419–29.ArticlePubMed

- 20. Takami Y, Yamamoto K, Arima H, Sakima A. Target blood pressure level for the treatment of elderly hypertensive patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Hypertens Res 2019;42:660–8.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 21. Dallaire-Theroux C, Quesnel-Olivo MH, Brochu K, Bergeron F, O’Connor S, Turgeon AF, et al. Evaluation of intensive vs standard blood pressure reduction and association with cognitive decline and dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2134553.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 22. Juraschek SP, Hu JR, Cluett JL, Ishak A, Mita C, Lipsitz LA, et al. Effects of intensive blood pressure treatment on orthostatic hypotension: a systematic review and individual participant-based meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2021;174:58–68.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 23. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 2018;71:e13–115.PubMed

- 24. Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M, et al. 2018 Practice guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension and the European Society of Cardiology: ESH/ESC Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension. J Hypertens 2018;36:2284–309.ArticlePubMed

- 25. Umemura S, Arima H, Arima S, Asayama K, Dohi Y, Hirooka Y, et al. The Japanese Society of Hypertension guidelines for the management of hypertension (JSH 2019). Hypertens Res 2019;42:1235–481.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 26. Kim HL, Lee EM, Ahn SY, Kim KI, Kim HC, Kim JH, et al. The 2022 focused update of the 2018 Korean Hypertension Society guidelines for the management of hypertension. Clin Hypertens 2023;29:11. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 27. Kim KI, Ihm SH, Kim GH, Kim HC, Kim JH, Lee HY, et al. 2018 Korean society of hypertension guidelines for the management of hypertension: part III: hypertension in special situations. Clin Hypertens 2019;25:19. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 28. Muller M, Smulders YM, de Leeuw PW, Stehouwer CD. Treatment of hypertension in the oldest old: a critical role for frailty? Hypertension 2014;63:433–41.ArticlePubMed

- 29. Forman DE, Maurer MS, Boyd C, Brindis R, Salive ME, Horne FM, et al. Multimorbidity in older adults with cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71:2149–61.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 30. Choi JY, Chun S, Kim H, Jung YI, Yoo S, Kim KI. Analysis of blood pressure and blood pressure variability pattern among older patients in long-term care hospitals: an observational study analysing the Health-RESPECT (integrated caRE Systems for elderly PatiEnts using iCT) dataset. Age Ageing 2022;51:afac018. ArticlePubMedPDF

- 31. Jung HW, Kim KI. Blood pressure variability and cognitive function in the elderly. Pulse (Basel) 2013;1:29–34.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by