The effects and side effects of liraglutide as a treatment for obesity

Article information

Abstract

The incidence of obesity is increasing throughout the world, including Korea. Liraglutide, the main purpose of which is glucose control, has recently gained significant attention due to its additional effect on weight loss. Liraglutide injections have been widely used as an important treatment for obese patients in Korea. In addition to weight loss, liraglutide has various other effects, such as prevention of cardiovascular disease. Despite its excellent effect on weight loss, notable side effects, such as nausea and vomiting, have also been associated with liraglutide. Despite these side effects, liraglutide has not been discontinued due to its beneficial effects on weight loss. Nonetheless, there are reports wherein patients did not experience weight loss upon taking the drug. As such, there is a possibility of liraglutide misuse and abuse. Therefore, physicians need to have a broad understanding of liraglutide and understand the advantages and disadvantages of liraglutide prescription.

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of obesity continues to increase worldwide, and Korea is no exception to this trend [1,2]. Obesity is associated with a variety of diseases, including type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, renal impairment, cancer, and cardiovascular disease. Thus, obesity increases medical costs and imposes a burden on public health [3,4]. According to the 2021 Obesity Fact Sheet published by the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity (KSSO), 36.3% of adults over 20 years of age were obese when obesity was defined as a body mass index (BMI) of 25 kg/m2 or more. The prevalence of obesity has consistently increased over the past 11 years, and a particularly sharp increase has been observed in men (46.2%) [5]. In addition, the risk of type 2 diabetes, other cardiovascular diseases, and cancer has increased in obese Korean patients, similar to the trends reported in other countries [5]. Therefore, the prevention of obesity through systematic management and active treatment of obese patients is important in the management of other related comorbidities.

The KSSO's 2020 Guidelines for the Management of Obesity recommend diet, exercise, and behavioral therapy as basic treatment methods for obesity, as well as pharmacological treatment and surgery in certain scenarios [6]. In patients with a BMI ≥25 kg/m2, pharmacological treatment should be considered when nonpharmacological treatments, such as diet, exercise, and behavioral therapy, fail to contribute to weight loss. If a patient does not lose more than 5% of his or her baseline weight within 3 months of initiating pharmacological treatment, it is recommended to either change or discontinue the drug [6]. The obesity drugs available in Korea include orlistat, a combination of naltrexone extended-release (ER) with bupropion ER, liraglutide, and a phentermine-topiramate ER combination. Among them, liraglutide, a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist (RA), is an injection with proven effects on weight loss. It is currently used as an important treatment for obesity in Korea. Therefore, this review was conducted to analyze the results of various clinical studies on the mechanism of action and weight loss effects of liraglutide and to summarize its side effects.

LIRAGLUTIDE AS AN ANTIOBESITY DRUG

In Korea, Xenical (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), a lipase inhibitor with the generic name of orlistat, was prescribed as a full-fledged antiobesity drug in the 2000s. Although Xenical was a high-selling obesity treatment at the time of its launch, its weight loss effect was not higher than placebo treatment (2.8%). Compliance with Xenical was poor due to frequent side effects, such as fatty stools, abdominal distension, flatus, and defecation incontinence. The naltrexone ER-bupropion ER combination, which appeared next, also showed no significant weight loss compared to placebo (3.2% to 5.2% per year), and patients often did not achieve the desired weight loss. In addition, this combination was not actively used for antiobesity treatment due to its side effects on the digestive system, such as nausea/vomiting, and various neurological side effects, such as dizziness and anxiety. Saxenda, a GLP-1 RA derivative with liraglutide as an active ingredient, was developed by Novo Nordisk (Bagsværd, Denmark). Saxenda was developed by varying the dose of Victoza, another brand-name diabetes drug containing liraglutide [7]. In a long-term clinical study, weight loss due to treatment with 0.3 mg of liraglutide was reported to be 5.4% to 6.0%, which was superior to that achieved using existing antiobesity drugs [8]. A real-world data analysis also reported that liraglutide had a greater effect on weight loss than orlistat [9].

MECHANISM OF ACTION OF LIRAGLUTIDE

GLP-1 is an incretin peptide hormone that is rapidly secreted from the small intestine when food is absorbed [10,11]. GLP-1 receptors are in various organs; in particular, GLP-1 receptors in the pancreas act in a glucose-dependent manner to stimulate insulin secretion and inhibit glucagon secretion [12,13]. In addition, GLP-1 stimulates anorexigenic neurons and inhibits orexigenic neurons, thereby increasing satiety, delaying gastric emptying, and decreasing appetite [14]. It also regulates food intake through direct effects on vagal afferent neurons in the digestive system [15]. GLP-1 RA-induced weight loss occurs through various mechanisms. In fact, postprandial GLP-1 levels rise after bariatric surgery (also known as metabolic surgery), which can improve glucose metabolism and affect weight loss [16].

GLP-1 has a very short half-life of 1.5 minutes when administered intravenously and 1.5 hours when administered subcutaneously [17]. To extend the half-life of GLP-1 RAs, liraglutide was acylated to prevent degradation by reversible binding to serum albumin, making it possible to administer a single subcutaneous dose daily [17]. Therefore, liraglutide is classified as a GLP-1 derivative with more than 90% sequence similarity to the human GLP-1 [18]. Liraglutide (Saxenda, 3.0 mg) is currently approved for the treatment of obesity in many countries, including Korea, and has a 97% sequence similarity to human GLP-1. The plasma concentration of liraglutide peaks 11 hours after subcutaneous administration and has a half-life of 13 hours [18].

THE CLINICAL EFFECTS OF LIRAGLUTIDE

Effects on weight loss

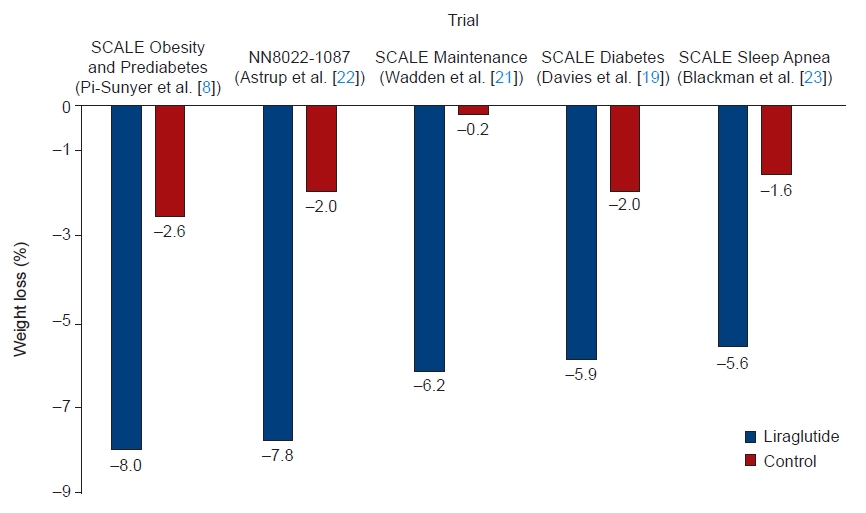

The safety and efficacy of liraglutide in weight loss have been reported in various studies such as the Satiety and Clinical Adiposity: Liraglutide Evidence (SCALE) program trial, a phase 3 study targeting 5,339 overweight or obese patients [19–22]. Before the start of each study, all subjects were asked to implement diet and exercise therapy (active physical activity for at least 150 minutes per week) through lifestyle modification counseling. A significantly greater mean weight loss was confirmed with liraglutide than with placebo across the various SCALE trials [8,19–21,23,24].

The SCALE Obesity and Prediabetes trial was the largest and longest-running study among the SCALE programs [8]. In a 56-week double-blind trial investigating the effect of liraglutide on weight loss, 2,487 adults with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or higher were administered liraglutide (experimental group), while 1,244 adults received placebo (control group). The individuals were observed for 56 weeks. At week 56, an average weight loss of 8.4±7.3 kg was observed in the liraglutide-administered group, while an average of 2.8±6.5 kg was observed in the placebo group (95% confidence interval, –6.0 to –5.1; P<0.001) [8]. Furthermore, in the liraglutide group, 63.2% of patients had a weight loss of 5% or more compared to baseline, versus only 27.1% in the control group (P<0.001). In the liraglutide group, 33.1% of participants had a weight loss of 10% or more, whereas this was the case for only 10.6% of patients in the control group (P<0.001) [8].

Among other studies in the SCALE program, the 56-week SCALE Diabetes trial confirmed the efficacy of liraglutide for weight management in overweight or obese patients and type 2 diabetes patients [19]. The SCALE Maintenance trial evaluated the efficacy of liraglutide for maintaining weight loss achieved during a low-calorie diet (1,200 to 1,400 kcal/day) in patients without diabetes for 56 weeks, showing a weight loss of 6.2% in the liraglutide group [21]. In addition, the SCALE Sleep Apnea trial evaluated the change in the apnea-hypopnea index after 32 weeks of liraglutide treatment in adults with obesity and moderate or severe obstructive sleep apnea, but not diabetes [23]. The placebo group showed an average weight loss of 1.6%, while the liraglutide group showed an average weight loss of 5.7%.

Subsequently, additional studies were conducted on the efficacy and safety of liraglutide for the treatment of obesity. The SCALE IBT trial compared the effects of intensive behavioral therapy (IBT) and liraglutide combination therapy with IBT and placebo for 56 weeks on weight loss in adults [24]. After 56 weeks, the IBT and liraglutide group showed a weight loss of 7.5%, while the IBT and placebo group showed a weight loss of 4.0% [24]. Additionally, in the liraglutide-treated group, 61.5% of the total patients showed a weight loss of 5% or more compared to baseline (versus 38.8% in the placebo group), and 30.5% of the total patients showed a weight loss of 10% or more compared to baseline [24]. The SCALE Insulin trial investigated the efficacy and safety of liraglutide in overweight or obese patients with type 2 diabetes treated with basal insulin and up to two oral antidiabetic drugs [25]. In a study conducted concurrently with IBT for 56 weeks, the liraglutide group showed a weight loss of 5.8% compared to baseline, whereas the control group showed a weight loss of 1.5% [25]. In addition, 51.8% of the liraglutide-administered group showed a weight loss of 5% or more compared to baseline, but the proportion in the control group was only 24.0% [25].

Studies have also reported the effects of liraglutide as a treatment for obesity in Koreans [26]. In a retrospective analysis of the weight loss effect of liraglutide in patients with an average BMI of 30.8 kg/m2, weight loss of 3.2±1.8 kg after 1 month, 4.5±2.3 kg after 2 months, 6.3±2.6 kg after 3 months, and 7.8±3.5 kg after 6 months was confirmed, and fat (–11.06%±10.4%) was reduced more than muscle (–3.56%±29.7%) [26]. In an analysis using real-world data, the superiority of liraglutide in terms of its effect on weight loss was underscored upon comparison with existing obesity treatment [9]. The effects of orlistat and liraglutide were retrospectively analyzed for 6 months in 500 patients with a BMI ≥30 kg/m2 or a weight-related disease [9]. The observed weight loss was 7.7 kg in the liraglutide-administered group and 3.3 kg in the orlistat-administered group [9]. In addition, more individuals lost at least 5% of their baseline weight with liraglutide (64.7%) than with orlistat (27.4%) [9]. Therefore, the weight loss effect of liraglutide, which was demonstrated in several clinical studies, was also confirmed through real-world evidence; in particular, its effect was found to be superior to that of orlistat. The effects of liraglutide administration on body weight in major studies are summarized and presented in Fig. 1 [8,19,21–23].

Effects on metabolic parameters

A 24-week cohort study investigated the effects of liraglutide on body composition [27]. This study was conducted on patients with type 2 diabetes who were overweight or obese with a hemoglobin A1c of 6% to 10%, and body composition-related indicators were measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry before and after 24 weeks of treatment [27]. In the analysis adjusted for age, sex, and duration of diabetes, liraglutide showed effects not only on BMI, but also on fat mass (–2.01 kg, P=0.015), fat mass index (–0.71 kg/m2, P=0.014), android fat (–1.72%, P=0.022), trunk fat (–1.52%, P=0.016), and waist circumference (–6.86 cm, P<0.001) [27]. Based on these significant changes in weight loss and body fat, the effects of liraglutide on various cardiometabolic risk factors have been reported.

The liraglutide group showed significant improvements in systolic blood pressure, waist circumference, hemoglobin A1c, total cholesterol, and triglycerides were observed in all phase 3 SCALE trials [8,19–21,23,24]. In the SCALE Insulin trial, a significant decrease in blood glucose and basal insulin requirement was observed in the liraglutide-administered group [25]. A study on polycystic ovary syndrome patients also showed that the weight loss effect of liraglutide was superior to that of metformin, an existing treatment [28]. Therefore, further studies evaluating the weight loss effect of liraglutide in various diseases accompanied by obesity are expected in the future.

Effects on cardiovascular prevention

Although the cardiovascular effects of liraglutide were not sufficiently validated in the SCALE trials, various data related to cardiometabolic risk and major adverse cardiovascular events were collected. These data were integrated and analyzed to evaluate the cardiovascular effects of liraglutide. The overall risk of cardiovascular events, calculated based on data from 5,908 patients, was lower in the liraglutide group than in the placebo group (treated group, 1.54 events per 1,000 person-years vs. placebo group, 3.83 events per 1,000 person-years; P=0.07) [29]. In another Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes: Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcome Results (LEADER) trial in which liraglutide (1.8 mg) was administered to patients at high risk of cardiovascular events with type 2 diabetes, the liraglutide group had a significantly lower incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events than the placebo group [30].

However, the patients included in the LEADER trial had type 2 diabetes and a higher risk of cardiovascular events than the patients included in the SCALE trial, and a liraglutide dose of 1.8 mg was administered in the LEADER trial. Therefore, additional studies are needed to determine the cardiovascular effects of liraglutide in obese patients. In addition, a follow-up study is needed to evaluate whether the benefits of liraglutide (1.8 mg) on the cardiovascular system in the LEADER trial reflect the direct effects of this GLP-1 RA or the effects of weight loss and improved blood sugar levels.

SIDE EFFECTS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

The most common side effects of liraglutide are gastrointestinal, such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, digestive disorders, abdominal pain, bloating, gastroesophageal reflux, dry mouth, and gastritis [31]. In addition, redness at the injection site, fatigue, lethargy, dizziness, and sleep disturbances have also been reported [31]. Liraglutide is also known to increase the levels of amylase and lipase and increase the risk of the development of gallstones [6]. Furthermore, 16% to 39% of patients treated with liraglutide complained of these side effects, whereas 4% to 14% of patients treated with placebo reported these adverse reactions [8,19]. Most of them were mild or transient at the start of treatment, and the likelihood of discontinuing the drug owing to side effects was reported to be low [8,19–21,23,24,32,33]. However, it should be explained to patients receiving liraglutide that nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, and digestive disorders may occur at the initial stage of drug administration and during the dose-escalation phase [8,19]. If vomiting is severe, sufficient fluid intake is recommended to prevent dehydration and renal dysfunction due to dehydration.

In a postmarketing survey, acute pancreatitis was observed in patients receiving liraglutide, and throughout the SCALE program, pancreatitis was observed in 0.3% of patients who received liraglutide versus 0.1% in the placebo group [31]. However, the risk of pancreatitis due to liraglutide administration was reported to be very low when 3,720 person-years were analyzed for all doses of liraglutide [31]. Gallbladder-related side effects, including acute cholecystitis, were more common in the liraglutide group than in the placebo group in the SCALE trials (cholelithiasis, 2.2% in the liraglutide group vs. 0.8% in the placebo group; cholecystitis, 0.8% in the liraglutide group vs. 0.4% in the placebo group) [8,19–21,23,24]. Based on this, the KSSO Guidelines for the Management of Obesity recommend that patients with a history of pancreatitis or currently suffering from pancreatitis must avoid liraglutide administration, and the occurrence of cholelithiasis should be monitored [6]. In fact, gallbladder disease and cholecystitis can occur in patients rapidly losing weight by any means, and this risk increases with greater weight loss. The incidence of gallbladder disease and cholecystitis in patients with sudden weight loss unrelated to liraglutide is known to vary substantially from 4.4% to 11.0% [34]. Since liraglutide is an antiobesity drug based on a drug that regulates blood glucose levels, it is important to observe the effect of liraglutide administration on blood glucose levels. In the SCALE Insulin trial, hypoglycemia was less common in the liraglutide group than in the placebo group: 742.3 cases per 100 patient-years in the liraglutide-treated group and 937.9 cases per 100 patient-years in the placebo group, using the American Diabetes Association's definition of hypoglycemia [25].

Liraglutide is contraindicated in pregnant women and in patients with medullary thyroid cancer, multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2, or a family history of those conditions. Although the evidence for the development of neoplastic tumors in obese patients treated with liraglutide is limited, a causal relationship between the occurrence of neoplastic tumors and liraglutide has not yet been established [35].

CONCLUSIONS

Liraglutide, a GLP-RA that is administered subcutaneously once a day, has shown significant effects on weight loss compared to the placebo group in various clinical studies. In addition to its effect on weight loss, liraglutide improved various cardiometabolic risk factors, such as lowering blood pressure, dyslipidemia, and blood glucose levels, which are closely related to obesity. In various clinical studies, serious side effects that require discontinuation of liraglutide administration did not occur, but digestive system side effects, such as nausea, vomiting, and other digestive disorders, were noted frequently. Although a clear causal relationship has not yet been established, liraglutide requires attention, as cholelithiasis and pancreatitis have been reported.

Therefore, when prescribing liraglutide, it is necessary to have a detailed discussion with patients about the expected clinical effects and side effects of the drug. This can lead to successful treatment of obesity. In the future, if the administration interval of the drug is increased or an oral dosage form becomes possible, patients' adherence to the medication is expected to increase. Eventually, liraglutide can be expected to show significant effects on weight loss in patients.

Notes

Ethical statements

Not applicable.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

This work was supported by a National Research Foundation (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (the Ministry of Science and ICT) (No. NRF-2021R1G1A1091471).

Author contributions

Conceptualization: all authors; Data curation: all authors; Formal analysis: all authors; Funding acquisition: HSK; Investigation: HSK; Methodology: HSK; Project administration: HSK; Resources: HSK; Software: HSK; Supervision: HSK; Validation: HSK; Visualization: JH; Writing–original draft: JH; Writing–review & editing: all authors.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.